William, you are a dear brother, a listener, counselor, friend.

William Hohri was the youngest of six children. I was William's older brother by two years. Sitting in the audience is Takuo Hohri, William's older brother by six years. Here are a few recollections of William's early life.

In 1930 with parents in a tuberculosis sanatorium, William and his siblings were sent to an orphanage. The first week there, an eleven year old child kitchen worker mistakenly spooned salt instead of sugar into all the breakfast porridges. Orphanage rule: If you don't eat up everything, you don't leave the table. After the first taste, only William refused to eat. He sat silently in front of the salt porridge for seven hours. He never ate it.

In 1934, with parents cured, William, now seven, and his siblings returned home to Sierra Madre. His favorite toys were the tool box hammer, wrench, screwdriver, pliers. William carefully took apart things around the house, and carefully put them together again. His greatest challenge: the wind-up alarm clock with its spring and many finely balanced gears.

In 1942, William, now 14, was a lead gymnast at North Hollywood High School. He performed with sure, powerful skill.

In the late 1940's, his university years, William met several unusual teachers. From memory, I recite the words of two.

Robert Maynard Hutchins: Feel free. Love truth. Be fearless. Speak truth, clear, short, to the point.

Reinhold Niebuhr: Man has been wounded by the arrows of God. Man's knowledge is ever incomplete, his moral vision often blurred. Still man's duty remains the continuing struggle for social justice.

Return to 1934. William attends his very first Christian church service. Now the Sunday school hour is over. Now all the children reassemble. Now all lift their voice in the hymn, "Work for the night is coming, when man's work is done."

"To see what is right and not to do it is cowardice." -- Confucius

Friday, November 26, 2010

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Exerpt about William Hohri from Frank Abe's Blog

Sunday, November 21, 2010 Thirty years ago, William Hohri picked up our Days of Remembrance movement here in Seattle and took us national. William's memorial service was today in Little Tokyo. Nice of Elaine Woo at the L.A. Times to call and ask for a quote. Martha Nakagawa offers exhaustive coverage of William's life and times in the Rafu Shimpo, and she still says she feels bad that she wasn't able to include William's earlier life in the Shonien and Manzanar's Children's Village. Thirty years ago, William Hohri picked up our Days of Remembrance movement here in Seattle and took us national. William's memorial service was today in Little Tokyo. Nice of Elaine Woo at the L.A. Times to call and ask for a quote. Martha Nakagawa offers exhaustive coverage of William's life and times in the Rafu Shimpo, and she still says she feels bad that she wasn't able to include William's earlier life in the Shonien and Manzanar's Children's Village. Saturday, November 13, 2010 William Hohri passed away Friday after a long illness. William was a seminal figure in changing the way we understand American history and Japanese American history. Like the Heart Mountain resisters he admired and chronicled, William stepped up to organize Japanese America and go to court to challenge the injustice of selective incarceration based solely on race. He was a leader, a lead plaintiff, an author and an artist, and he will be deeply missed. Saturday, November 13, 2010 William Hohri passed away Friday after a long illness. William was a seminal figure in changing the way we understand American history and Japanese American history. Like the Heart Mountain resisters he admired and chronicled, William stepped up to organize Japanese America and go to court to challenge the injustice of selective incarceration based solely on race. He was a leader, a lead plaintiff, an author and an artist, and he will be deeply missed.William got the government’s attention with his lawsuit seeking monetary damages for illegal wartime incarceration. What seemed at first to be a quixotic action helped focus Congress on passing a real redress bill before “Hohri et.al. vs. U.S “ could come to trial in federal court. After the first successful Days of Remembrance at the Puyallup Fairgrounds and the Portland Expo Center, and the national Open Letter to Hayakawa, we in the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee were contacted by this guy out of Chicago who wanted to keep the momentum for genuine redress going. At a time when the Nikkei in Congress and national JACL were calling for a commission to study the issue, William said it was time to organize for something better. In that, he shared the same instincts as Harry Ueno, Kiyoshi Okamoto, and Frank Emi.  The one footnote I can claim in William’s legend is an edit. William, Shosuke Sasaki, Henry Miyatake and others of us were sitting around the table in our redress “war room,” the conference room in the law offices of Ron Mamiya and Rod Kawakami at 7th and Jackson – the same block where John Okada imagined Ichiro Yamada’s grocery store to be in his novel No No Boy – trying to forge the name for this new national organization that would work around JACL and lobby Congress directly for a redress bill that provided for direct compensation to incarcerees. We spitballed a number of ideas, taking awhile to decide that “Japanese American” should be included in the name, and came around to “National Coalition for Japanese American Redress,” but I thought that sounded too … sixties, and after all here we had progressed to the tail end of the 70’s. I suggested we call it a “National Council” and Shosuke quickly agreed that sounded loftier, and we were on our way. William adopted Frank Fujii’s ichi-ni-san barbed wire logo from the Days of Remembrance for the masthead of his own monthly NCJAR newsletter, keeping the spirit alive. The one footnote I can claim in William’s legend is an edit. William, Shosuke Sasaki, Henry Miyatake and others of us were sitting around the table in our redress “war room,” the conference room in the law offices of Ron Mamiya and Rod Kawakami at 7th and Jackson – the same block where John Okada imagined Ichiro Yamada’s grocery store to be in his novel No No Boy – trying to forge the name for this new national organization that would work around JACL and lobby Congress directly for a redress bill that provided for direct compensation to incarcerees. We spitballed a number of ideas, taking awhile to decide that “Japanese American” should be included in the name, and came around to “National Coalition for Japanese American Redress,” but I thought that sounded too … sixties, and after all here we had progressed to the tail end of the 70’s. I suggested we call it a “National Council” and Shosuke quickly agreed that sounded loftier, and we were on our way. William adopted Frank Fujii’s ichi-ni-san barbed wire logo from the Days of Remembrance for the masthead of his own monthly NCJAR newsletter, keeping the spirit alive. We were in Washington, DC for the first round of hearings of the Congressional commission in 1981, when as our informal media coordinator William casually told me he had turned down an invitation from ABC News to appear on something called “Nightline,” because it was late and he was tired and he thought it was a local broadcast. I was horrified and chewed him out for the lost opportunity to raise money for what was by then his class-action lawsuit; ABC used JACL district governor Tom Kometani instead. At the hearings where even I wore a suit and tie, William insisted on testifying to Congress in his Frank Fujii ichi-ni-san T-shirt, with the yellow redress button in his lapel. Like myself, once redress was won and American history had been cured, William turned his attention from holding the government accountable to holding our wartime community leaders accountable and exposing the story of the largest organized resistance to wartime incarceration. Besides his well-known REPAIRING AMERICA: AN ACCOUNT OF THE MOVEMENT FOR JAPANESE AMERICAN REDRESS, William self-published three other books. He compiled and introduced RESISTANCE, a book with first-person accounts from the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee. He published a bound edition of the notorious LIM REPORT, which chronicled the wartime collaboration of JACL leaders in their own words. He self-published a novel, MANZANAR RITES, that made fiction of the insurgency of Kitchen Workers Union leader Harry Ueno, the riot sparked by unrest at camp conditions and the JACL’s call for drafting the Nisei out of camp, and which climaxes with the Army’s fatal shooting of two young men. Ever the historian, William expresses relief in an end note that he did not have to footnote his sources. My condolences to Yuriko and their family. The family is planning a celebration of William’s life at the Fukui Mortuary in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. Frank Emi and Yosh Kuromiya are being asked to speak. More details as they become available. |

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Message to Association for Asian American Studies from Phil Tajitsu Nash

Dear family and friends of WMH,

The following was just sent via listserv to all members of the Association for Asian American Studies (AAAS). William well knew that participating in history is just the first step. Preserving a true account of what happened is sometimes just as important.

Peace,

Phil Tajitsu Nash

+++++++++++++++++++++++

William Hohri Dies at 83

William Hohri's story represents a significant part of the larger Japanese American redress story, but it is often lost in the one-dimensional way history is remembered. We honor the victors who pushed redress across the finish line in Congress in 1988, or those such as Fred Korematsu who won their coram nobis cases, but we don't always remember to honor those, like William Hohri, who tried other avenues that did not prevail (although, as a lobbyist in Washington in the 1980s, I can assure you that the threat of a class action victory was a factor in Congress pushing for a legislated payout).

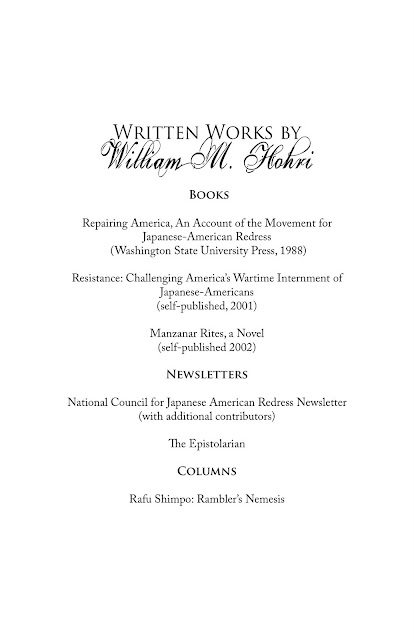

If you have not had the chance, please look up William's Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress and Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese-Americans. And if you are teaching Korematsu and other Japanese American cases in your classes, please remind the students about the multi-faceted way that law, legislation, and community organizing intersect in social justice cases. Race, Rights and Reparation by Eric Yamamoto et al is a great starting place for seeing the Hohri case in this context.

If you want to send a note to the Hohri family, please go to http://williamhohri.blogspot.

Related news articles:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/

http://articles.latimes.com/

http://rafu.com/news/2010/11/

The following was just sent via listserv to all members of the Association for Asian American Studies (AAAS). William well knew that participating in history is just the first step. Preserving a true account of what happened is sometimes just as important.

Peace,

Phil Tajitsu Nash

+++++++++++++++++++++++

William Hohri Dies at 83

William Hohri's story represents a significant part of the larger Japanese American redress story, but it is often lost in the one-dimensional way history is remembered. We honor the victors who pushed redress across the finish line in Congress in 1988, or those such as Fred Korematsu who won their coram nobis cases, but we don't always remember to honor those, like William Hohri, who tried other avenues that did not prevail (although, as a lobbyist in Washington in the 1980s, I can assure you that the threat of a class action victory was a factor in Congress pushing for a legislated payout).

If you have not had the chance, please look up William's Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress and Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese-Americans. And if you are teaching Korematsu and other Japanese American cases in your classes, please remind the students about the multi-faceted way that law, legislation, and community organizing intersect in social justice cases. Race, Rights and Reparation by Eric Yamamoto et al is a great starting place for seeing the Hohri case in this context.

If you want to send a note to the Hohri family, please go to http://williamhohri.blogspot.

Related news articles:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/

http://articles.latimes.com/

http://rafu.com/news/2010/11/

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Sasha Hohri

Seasons for Pa

Spring - New, Bright, Sparks

Long walks

The Museum of Science & Industry

Beach on Lake Michigan

Go Player

Bears Fan

Symbolic Logic

Car Parts - SH Arnold's

Conducting Bach on LP

Singing Loudly

Reading Scientific American

Doing jigsaw puzzles

Morris Minor

Mini Cooper

Dick Gregory

Stand Frieberg

Tom Lehrer

bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Church activism and leadership Christian Fellowship Church

Lay leader, Rock River Conference United Methodist Church

Christmas in Japan

Soldier Field - Stokley Carmichael - Martin Luther King Jr.

Milwaukee Wisconsin - Go Go Groppee

Civil Rights Inspiration

Liberation Chapter - Chicago JACL

caps and bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Summer - Blooming Partnerships

Congressman Mike Lowry

Courts not Congress

Accuracy of detail

Rule of Law - The Constitution

Michi Weglyn

Aiko Hertzig-Yoshinaga

Not mean or personal

Rather persistent and vocal

National Council for Japanese American Redress

Class Action Suit - main named plaintiff

Ronin

To the Supreme Court

"What is the difference between banishment and killing?" - Justice Thurgood Marshall

The Epistolarian

Repairing America

Manzanar Rites

Rambler's Nemesis

Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans

Up at 5:30 in bed at 8

Going to work everyday

caps and bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Autumn - Letting Go

Speaking

Writing

caps

holding forth

reading

laughter

surrounded by beauty, love and kindness

surrounded by beauty, love and kindness

Yuriko, Sylvia and Ed

breathing out and out

breathing out and out

into the unknown mystery of winter

Spring - New, Bright, Sparks

Long walks

The Museum of Science & Industry

Beach on Lake Michigan

Go Player

Bears Fan

Symbolic Logic

Car Parts - SH Arnold's

Conducting Bach on LP

Singing Loudly

Reading Scientific American

Doing jigsaw puzzles

Morris Minor

Mini Cooper

Dick Gregory

Stand Frieberg

Tom Lehrer

bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Church activism and leadership Christian Fellowship Church

Lay leader, Rock River Conference United Methodist Church

Christmas in Japan

Soldier Field - Stokley Carmichael - Martin Luther King Jr.

Milwaukee Wisconsin - Go Go Groppee

Civil Rights Inspiration

Liberation Chapter - Chicago JACL

caps and bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Summer - Blooming Partnerships

Congressman Mike Lowry

Courts not Congress

Accuracy of detail

Rule of Law - The Constitution

Michi Weglyn

Aiko Hertzig-Yoshinaga

Not mean or personal

Rather persistent and vocal

National Council for Japanese American Redress

Class Action Suit - main named plaintiff

Ronin

To the Supreme Court

"What is the difference between banishment and killing?" - Justice Thurgood Marshall

The Epistolarian

Repairing America

Manzanar Rites

Rambler's Nemesis

Resistance: Challenging America's Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans

Up at 5:30 in bed at 8

Going to work everyday

caps and bowties

holding forth

reading

great laughs

Autumn - Letting Go

Speaking

Writing

caps

holding forth

reading

laughter

surrounded by beauty, love and kindness

surrounded by beauty, love and kindness

Yuriko, Sylvia and Ed

breathing out and out

breathing out and out

into the unknown mystery of winter

Thank you to those who helped with the memorial service

Thank you to Aiko Hertzig-Yoshinaga, Peter Taytay, Jeanie Kim, Sharon Yamato, Kate Bergh, Hilarie Friedlander, Ron Butchart, Chiyo Takarabe, Ann Matsushima Chiu.

Complete Library of the Epistolarian and Rambler's Nemesis

zip file of full Epistolarian and Rambler's Nemesis Columns

Click the above link for a zip file of William Hohri's columns: The Epostolarian and Rambler's Nemesis. Thank you to Diana Morita Cole for compiling the articles.

Click the above link for a zip file of William Hohri's columns: The Epostolarian and Rambler's Nemesis. Thank you to Diana Morita Cole for compiling the articles.

Takamichi "Taka" Go

Translator of William Hohri's books into Japanese.

Dear Mrs. Hohri,

I would like to send you my great appreciation for your husband, Mr.

William Minoru Hohri. It was a year after my internship at Manzanar

National Historic Site. I started reading different books on

Japanese-American history. One of them was "Repairing America: An

Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress." Then, I began

reading "Manzanar Rites." Both books were written by him. I was also

impressed with the National Council for Japanese-American Redress,

which he led for years and years. I always feel thankful for him. He

not only did a lot of important things for Japanese-American

communities through the nation, he also "paved" a road to study the

history of Japanese-Americans for me. I will never forget what he has

done for Japanese-Americans. And again, I would like to send Mr.

William Minoru Hohri a great appreciation for many things that he did

in his entire life.

Thank you very much, Ariga to Gozai masu,

Takamichi "Taka" Go

Dear Mrs. Hohri,

I would like to send you my great appreciation for your husband, Mr.

William Minoru Hohri. It was a year after my internship at Manzanar

National Historic Site. I started reading different books on

Japanese-American history. One of them was "Repairing America: An

Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress." Then, I began

reading "Manzanar Rites." Both books were written by him. I was also

impressed with the National Council for Japanese-American Redress,

which he led for years and years. I always feel thankful for him. He

not only did a lot of important things for Japanese-American

communities through the nation, he also "paved" a road to study the

history of Japanese-Americans for me. I will never forget what he has

done for Japanese-Americans. And again, I would like to send Mr.

William Minoru Hohri a great appreciation for many things that he did

in his entire life.

Thank you very much, Ariga to Gozai masu,

Takamichi "Taka" Go

Monday, November 22, 2010

Frank Chin

My friends told me not to say what I intended because, as one wrote:

"Defiance and Justice, and you may be right in what you say but your remarks appear to attack and belittle allies to the cause at a time when we should be coming together at least for one moment of respect before going back to debating the great questions of our time.

"But you to try to egg on your audience by calling people who have contributed to unearthing the truth about the camps and the JACL betrayal timid, or cowards (because they did not name names as Hohri has done) antagonizes rather than inspires the very people who care about carrying this torch forward. It's worse than a roughing the passer penalty. You hurt your own credibility by appearing to tear down the reputations of fighters of this injustice (Weglyn, Omori and others each in their own way). , I would attend the celebration if I could. I agree it's a bad day at Black Rock - and I have seen the movie. But I would extoll the virtues of the hero without pointing out the deficiencies of fellow travelers in this particular venue. Perhaps at another time, another place."

I told my friends what I told the JACL, the Resisters and William Hohri….that if I find and verify evidence that they were not what they said they were, I wouldn't hesitate to set it to words. I looked for years and luckily found the resisters were straight with me. And JACL save Dr. Clifford Uyeda was not. William Hohri was straighter than straight with me. In fact, he didn't hesitate to tell me I was wrong, when he disagreed with me. And he disagreed mightily with me concerning the JACL.

Wiilliam Hohri’s column onthe Monument was the first instance of a Japanese American naming Mike Masaoka the leader of a Japanese American betrayal. When he did that, all his supporters let out a collective "whew!" and felt a little braver than they'd been in public, in print, in their works. His straight talk, coming when it did, puts all the work by Japanese Americans protesting the camps, the JACL , the case for and against the resisters in context with Japanese American ideals and the spoken truth..

Would the Founding Fathers of American democracy, be the founding Fathers, would the Declaration of Independence, be the defining document it is, and the US Constitution be model for governing men it is, if George Washington had accepted the crown as King of the United States and dashed all those good words to dust? No.

Would he be “the First in war, first in peace, first in hearts of men" if he had accepted a lifetime appointment as President, instead of the two terms he served? No. His behavior made the ideals expressed by the Founding Fathers, the Declaration of Independence, the US Consititution real.

Would MOBY DICK, or THE WHALE, about a motley crew of greedy ne’re do wells, or the paranoid writing of a dope fiend Edgar Allen Poe, or the homosexual battlefield nurse Walt Whitman or any American be read today if Abraham Lincoln had not kept the union together, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves and won the Civil War?

I am not attacking my friend Lawson Inada or the work of Michi Weglyn, or timidity of Emiko Omori, and Frank Abe, or the novel of David Mura. I ‘m saying , as a critic , that their work will be remembered because William Hohri made the whole of Japanese American history crystal clear by saying what no other Japanese American dared say in public..

I should be talking to the JACL not at Bill’s funeral, I’ve been told. Bill and Michi’s friends are the wrong audience. I yield to the voice of people..

You are the Japanese American people. You are the real people.

I'm merely a writer, a Chinaman, a witness, a messenger. A Crow scout reporting to the Sioux. I will defer my report to the Hohri e-mail., because this scout does not want to be skinned alive.

But, as the scout, I have to say: I have seen Custer. He's just over that ridge about a mile and half and riding this way very hard and very fast.. William Hohri your visionary Sitting Bull and activist Crazy Horse are dead. The real people can ride to meet Custer or run for their lives. If you decide to meet Custer, I am your scout, and will write what I witnessed. If you decide to run for your lives, I am your scout, and will write what I witnessed. And if Custer overruns you, I will write that too, because that is what scouts are supposed to do.

"Defiance and Justice, and you may be right in what you say but your remarks appear to attack and belittle allies to the cause at a time when we should be coming together at least for one moment of respect before going back to debating the great questions of our time.

"But you to try to egg on your audience by calling people who have contributed to unearthing the truth about the camps and the JACL betrayal timid, or cowards (because they did not name names as Hohri has done) antagonizes rather than inspires the very people who care about carrying this torch forward. It's worse than a roughing the passer penalty. You hurt your own credibility by appearing to tear down the reputations of fighters of this injustice (Weglyn, Omori and others each in their own way). , I would attend the celebration if I could. I agree it's a bad day at Black Rock - and I have seen the movie. But I would extoll the virtues of the hero without pointing out the deficiencies of fellow travelers in this particular venue. Perhaps at another time, another place."

I told my friends what I told the JACL, the Resisters and William Hohri….that if I find and verify evidence that they were not what they said they were, I wouldn't hesitate to set it to words. I looked for years and luckily found the resisters were straight with me. And JACL save Dr. Clifford Uyeda was not. William Hohri was straighter than straight with me. In fact, he didn't hesitate to tell me I was wrong, when he disagreed with me. And he disagreed mightily with me concerning the JACL.

Wiilliam Hohri’s column onthe Monument was the first instance of a Japanese American naming Mike Masaoka the leader of a Japanese American betrayal. When he did that, all his supporters let out a collective "whew!" and felt a little braver than they'd been in public, in print, in their works. His straight talk, coming when it did, puts all the work by Japanese Americans protesting the camps, the JACL , the case for and against the resisters in context with Japanese American ideals and the spoken truth..

Would the Founding Fathers of American democracy, be the founding Fathers, would the Declaration of Independence, be the defining document it is, and the US Constitution be model for governing men it is, if George Washington had accepted the crown as King of the United States and dashed all those good words to dust? No.

Would he be “the First in war, first in peace, first in hearts of men" if he had accepted a lifetime appointment as President, instead of the two terms he served? No. His behavior made the ideals expressed by the Founding Fathers, the Declaration of Independence, the US Consititution real.

Would MOBY DICK, or THE WHALE, about a motley crew of greedy ne’re do wells, or the paranoid writing of a dope fiend Edgar Allen Poe, or the homosexual battlefield nurse Walt Whitman or any American be read today if Abraham Lincoln had not kept the union together, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves and won the Civil War?

I am not attacking my friend Lawson Inada or the work of Michi Weglyn, or timidity of Emiko Omori, and Frank Abe, or the novel of David Mura. I ‘m saying , as a critic , that their work will be remembered because William Hohri made the whole of Japanese American history crystal clear by saying what no other Japanese American dared say in public..

I should be talking to the JACL not at Bill’s funeral, I’ve been told. Bill and Michi’s friends are the wrong audience. I yield to the voice of people..

You are the Japanese American people. You are the real people.

I'm merely a writer, a Chinaman, a witness, a messenger. A Crow scout reporting to the Sioux. I will defer my report to the Hohri e-mail., because this scout does not want to be skinned alive.

But, as the scout, I have to say: I have seen Custer. He's just over that ridge about a mile and half and riding this way very hard and very fast.. William Hohri your visionary Sitting Bull and activist Crazy Horse are dead. The real people can ride to meet Custer or run for their lives. If you decide to meet Custer, I am your scout, and will write what I witnessed. If you decide to run for your lives, I am your scout, and will write what I witnessed. And if Custer overruns you, I will write that too, because that is what scouts are supposed to do.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Wilbur Sato & Yukikazu Nagashima

Thank you, Yuriko, for the privilege and honor of participating in the celebration of William’s life.

With you a part of me hath passed away;

For in the peopled forest of my mind

A tree made leafless by this wintry wind

Shall never don again its green array.

Chapel and fireside, country road and bay,

Have something of their friendliness resigned;

Another, if I would, I could not find,

And I am grown much older in a day.

But yet I treasure in my memory

Your gift of charity, and young heart’s ease,

And the dear honor of your amity;

For these once mine, my life is rich with these.

And I scarce know which part may greater be —

What I keep of you, or you rob from me.

William Hohri was a remarkable man with monumental accomplishments. But what is most remarkable is his triumph over adversity.

William Hohri was a child in the period of our history when we lived in segregated neighborhoods, had segregated schools, had discrimination in college entrance requirements, had job discrimination, had anti-miscegenation laws and discrimination in public accommodations. We lived during a time of hurtful and humiliating prejudice.

William’s fight for equality and human dignity for all Americans was an important part of his triumph over the pain and humiliation of that period.

William Hohri was also a child of the Great Depression where massive unemployment, grinding poverty and a lack of adequate social services and healthcare took a terrible toll on the poor and minority communities.

William was a victim of enormous poverty. His parents were stricken with tuberculosis and confined in a sanitarium. As a result, William was separated from his parents and placed in the Shonien orphanage. This trauma was the most painful of all the consequences of the oppression of poverty.

But William’s sense of gaman and ganbatte and sheer will to survive were part of the experiences that gave him the strength of character that enabled him to provide the leadership for the National Council for Japanese American Redress.

His life was also an essential lesson that health and human services must be included in our fight for justice and the triumph over adversity.

Perhaps the greatest adversity that William had to overcome was the horrendous incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps. The entire Japanese American community was affected, which led to impoverishment, humiliation, alienation, loss of property, devaluation of culture and language, decimation of communities, the destruction of our Constitutional rights, and the failure of the Supreme Court to uphold the Constitution and protect our civil rights.

William’s life of community activism for civil rights was a preparatory step that created a foundation for his role as leader of NCJAR.

William Hohri was brilliant in his strategy to use the federal court system to secure redress for Constitutional violations since the courts have the ultimate duty to protect and uphold Constitutional rights. It was especially appropriate since the courts had failed to protect our rights in the Fred Korematsu case. The wisdom of the strategy was also a presage to future litigants to use the courts to protect their rights.

Ultimately, this strategy was the hammer that influenced Congress to pass the redress legislation.

William’s work in the redress movement was his final triumph over the great adversities of his life.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light where the hours are suns

Endless and singing.…

Near the snow, near the sun, in the highest fields

See how these names are feted by the waving grass

And by the streamers of white cloud

And whispers of wind in the listening sky.

The names of those who in their lives fought for life

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s centre.

Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun,

And left the vivid air signed with their honour.

With You a Part of Me

By George Santayana

With you a part of me hath passed away;

For in the peopled forest of my mind

A tree made leafless by this wintry wind

Shall never don again its green array.

Chapel and fireside, country road and bay,

Have something of their friendliness resigned;

Another, if I would, I could not find,

And I am grown much older in a day.

But yet I treasure in my memory

Your gift of charity, and young heart’s ease,

And the dear honor of your amity;

For these once mine, my life is rich with these.

And I scarce know which part may greater be —

What I keep of you, or you rob from me.

William Hohri was a remarkable man with monumental accomplishments. But what is most remarkable is his triumph over adversity.

William Hohri was a child in the period of our history when we lived in segregated neighborhoods, had segregated schools, had discrimination in college entrance requirements, had job discrimination, had anti-miscegenation laws and discrimination in public accommodations. We lived during a time of hurtful and humiliating prejudice.

William’s fight for equality and human dignity for all Americans was an important part of his triumph over the pain and humiliation of that period.

William Hohri was also a child of the Great Depression where massive unemployment, grinding poverty and a lack of adequate social services and healthcare took a terrible toll on the poor and minority communities.

William was a victim of enormous poverty. His parents were stricken with tuberculosis and confined in a sanitarium. As a result, William was separated from his parents and placed in the Shonien orphanage. This trauma was the most painful of all the consequences of the oppression of poverty.

But William’s sense of gaman and ganbatte and sheer will to survive were part of the experiences that gave him the strength of character that enabled him to provide the leadership for the National Council for Japanese American Redress.

His life was also an essential lesson that health and human services must be included in our fight for justice and the triumph over adversity.

Perhaps the greatest adversity that William had to overcome was the horrendous incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps. The entire Japanese American community was affected, which led to impoverishment, humiliation, alienation, loss of property, devaluation of culture and language, decimation of communities, the destruction of our Constitutional rights, and the failure of the Supreme Court to uphold the Constitution and protect our civil rights.

William’s life of community activism for civil rights was a preparatory step that created a foundation for his role as leader of NCJAR.

William Hohri was brilliant in his strategy to use the federal court system to secure redress for Constitutional violations since the courts have the ultimate duty to protect and uphold Constitutional rights. It was especially appropriate since the courts had failed to protect our rights in the Fred Korematsu case. The wisdom of the strategy was also a presage to future litigants to use the courts to protect their rights.

Ultimately, this strategy was the hammer that influenced Congress to pass the redress legislation.

William’s work in the redress movement was his final triumph over the great adversities of his life.

I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great

By Stephen Spender

I think continually of those who were truly great. Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light where the hours are suns

Endless and singing.…

Near the snow, near the sun, in the highest fields

See how these names are feted by the waving grass

And by the streamers of white cloud

And whispers of wind in the listening sky.

The names of those who in their lives fought for life

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s centre.

Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun,

And left the vivid air signed with their honour.

Yosh and Irene Kuromiya

William always enjoyed good food. We were at a Chinese restaurant

in W.LA for a birthday party. Here comes his favorite chocolate cake

with candles for him to blow out. The surprise was the dusting of chocolate

powder on the cake that enshrouded him and the entire table when he blew out the candles.

We all enjoyed a good laugh along with the excellent Chinese food and wonderful company.

We will miss his wry sense of humor and intellect.

Irene Kuromiya

*****************************************************

William Minoru Hohri was a man who loved to share.

William Minoru Hohri was a man of ideas.

William Minoru Hohri loved to share his ideas.

We would talk on the phone for hours.

That is, he would talk and I would listen.

On one such occasion, during a lull in the conversation,

I suddenly realized the brilliance of what he was saying.

I took the rare opportunity to share my discovery with William.

That s exactly what I told you twenty minutes ago! he complained,

and abruptly hung up the phone.

I know. I explained to the dial tone at the other end of the line.

I only wanted to assure him that his words had finally found their mark.

William Hohri always had the first and the last word,

and that is as it should be, as his ideas were always in the interest

for the betterment of all of mankind.

William Minoru Hohri was a man who loved to share.

Yosh Kuromiya

in W.LA for a birthday party. Here comes his favorite chocolate cake

with candles for him to blow out. The surprise was the dusting of chocolate

powder on the cake that enshrouded him and the entire table when he blew out the candles.

We all enjoyed a good laugh along with the excellent Chinese food and wonderful company.

We will miss his wry sense of humor and intellect.

Irene Kuromiya

*****************************************************

William Minoru Hohri was a man who loved to share.

William Minoru Hohri was a man of ideas.

William Minoru Hohri loved to share his ideas.

We would talk on the phone for hours.

That is, he would talk and I would listen.

On one such occasion, during a lull in the conversation,

I suddenly realized the brilliance of what he was saying.

I took the rare opportunity to share my discovery with William.

That s exactly what I told you twenty minutes ago! he complained,

and abruptly hung up the phone.

I know. I explained to the dial tone at the other end of the line.

I only wanted to assure him that his words had finally found their mark.

William Hohri always had the first and the last word,

and that is as it should be, as his ideas were always in the interest

for the betterment of all of mankind.

William Minoru Hohri was a man who loved to share.

Yosh Kuromiya

Tsuya Hohri Yee

Hello and welcome everyone. My name is Tsuya Yee, and I’m one of William Hohri’s granddaughters.

I always knew he was special and brave, but I only realized the full implications of this when I went to college at UC Santa Cruz and met other yonsei. As a native New Yorker from Chinatown, I didn’t grow

up around a lot of other Japanese American families. In college, many of my yonsei classmates were learning about Japanese American internment for the first time in Asian American studies classes. They

confided in me the same story over and over, “no one talked about camp, it’s taboo,” and some even talked about feeling ashamed over that experience. I listened closely, sympathetically… and would then

reply, “what??” “what do you mean no one talked about it? you didn’t grow up hearing terms like “sovereign immunity, mass incarceration, reparations, No-No boys, day of remembrance” around your new year’s dinner table?” “Why are you ashamed?” I asked, “what the government did to us was wrong, it wasn’t our fault.” I later realized that my experience was really unique because I had Nisei grandparents who talked about it and a sansei parent who was a leader in the redress movement. And while I could never completely bypass the pain that comes with the internment experience, because of my early and candid exposure to the issue throughout my childhood, I was poised at a very young age to speak out about it, and help others heal.

Another curious thing I learned in college was that “Nisei are the quiet Americans.” I thought, I don’t know which Nisei they are talking about but all of my memories are to the contrary - my family

talks loudly, laughs loudly, lives boldly and speaks directly. My grandpa most of all.

What I now know is that I was absorbing important lessons from him, modeled through his manner and actions – stand up for yourself, speak up, make demands on those who do you wrong, build coalitions with others for help, be curious and engaged in the world, take pleasure in many things, words are a tool – read and write constantly,

And lastly, never stop talking and sharing your ideas and thoughts – they matter.

I have many personal memories, like his pleasure at telling me that he was wearing the same shirt to Sylvia and Ed’s wedding that he wore to his own wedding; his scoffing at my excitement over

traveling to japan to find my roots – his comments were along the lines of “I don’t think you’re going to find any “roots” over there. Why not go to China? That’s an amazing place – they invented the

printing press!” Or the many birthday and holiday cards to me from grandma and grandpa signed “Love, Grandma Yuriko” and “Peace, WMH.”

I’ll treasure my memories of you, do my best to follow your example, and honor you always by never forgetting you.

I always knew he was special and brave, but I only realized the full implications of this when I went to college at UC Santa Cruz and met other yonsei. As a native New Yorker from Chinatown, I didn’t grow

up around a lot of other Japanese American families. In college, many of my yonsei classmates were learning about Japanese American internment for the first time in Asian American studies classes. They

confided in me the same story over and over, “no one talked about camp, it’s taboo,” and some even talked about feeling ashamed over that experience. I listened closely, sympathetically… and would then

reply, “what??” “what do you mean no one talked about it? you didn’t grow up hearing terms like “sovereign immunity, mass incarceration, reparations, No-No boys, day of remembrance” around your new year’s dinner table?” “Why are you ashamed?” I asked, “what the government did to us was wrong, it wasn’t our fault.” I later realized that my experience was really unique because I had Nisei grandparents who talked about it and a sansei parent who was a leader in the redress movement. And while I could never completely bypass the pain that comes with the internment experience, because of my early and candid exposure to the issue throughout my childhood, I was poised at a very young age to speak out about it, and help others heal.

Another curious thing I learned in college was that “Nisei are the quiet Americans.” I thought, I don’t know which Nisei they are talking about but all of my memories are to the contrary - my family

talks loudly, laughs loudly, lives boldly and speaks directly. My grandpa most of all.

What I now know is that I was absorbing important lessons from him, modeled through his manner and actions – stand up for yourself, speak up, make demands on those who do you wrong, build coalitions with others for help, be curious and engaged in the world, take pleasure in many things, words are a tool – read and write constantly,

And lastly, never stop talking and sharing your ideas and thoughts – they matter.

I have many personal memories, like his pleasure at telling me that he was wearing the same shirt to Sylvia and Ed’s wedding that he wore to his own wedding; his scoffing at my excitement over

traveling to japan to find my roots – his comments were along the lines of “I don’t think you’re going to find any “roots” over there. Why not go to China? That’s an amazing place – they invented the

printing press!” Or the many birthday and holiday cards to me from grandma and grandpa signed “Love, Grandma Yuriko” and “Peace, WMH.”

I’ll treasure my memories of you, do my best to follow your example, and honor you always by never forgetting you.

Rev. Martin Deppe

William Hohri, A Memorial Tribute

William Hohri is an American hero. His life work was the repairing of America, and he succeeded by leading one of the most radical social justice movements culminating in redress almost half a century later for Japanese-American survivors of the illegal and unconstitutional concentration camps set up at the outbreak of WWII. Bill was 14 years old when he and his family were locked up at the Manzanar Camp in eastern California.

Bill did not forget that humiliating experience. That was still in the background when his local church in Chicago elected him a member of the regional body, the Northern Illinois Conference of the United Methodist Church. At these annual meetings Bill began to find his voice on social issues. This was in the late sixties, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the American war in Vietnam. Bill chaired the Peace Division of the Conference Board of Christian Social Concerns, which I chaired and he also attended Renewal Caucus meetings where he sharpened his skills in political debate and in organizing around justice issues. Later he told me these experiences helped prepare him for the redress fight which

opened up for him just a few years later.

Bill had quick intelligence, an indomitable spirit and an uncommon courage. In the words of our long- time colleague, Rev. Gregory Dell, Bill was “in life, a giant of faithfulness and persistence.” I remember joining Bill, Yuriko, and their young daughters, Sasha and Sylvia for a car ride to Milwaukee to join an open housing march led by the local civil rights leader, Father Groppi. The marchers were predominantly African American. Along the route crowds of Caucasians shouted at us all manner of epithets, including “White Power.” Getting exasperated, Bill shouted back at them, “Yellow Power!” At Bill’s invitation I was privileged to join a team of Methodists, Bishop Jesse DeWitt and Revs. Martha Coursey and Gregory Dell, in testifying at the Chicago hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in late 1981. We Chicago area Methodists were proud of Bill and honored to be part of his national effort. Later, on one of his many speaking tours, as Chair of the National Council for Japanese American Redress, Bill did a radio show in Indiana. After his presentation he took calls from the radio audience and one male caller blurted out: “You sound like a Jap lover.” Bill was so stunned he was speechless, something unusual for him by this time. The next Sunday he reported to his congregation, Parish of the Holy Covenant, on his week’s tour and confessed that he should have responded to the caller, “Yes, I loved my Jap mother, my Jap father and the rest of my Jap family.”

The movement had highs and lows, but through it all Bill had the vision, courage and perseverance to carry on against unexpected opposition and tremendous odds, leading to victory, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, offering $20,000 to each internee of Japanese descent. The Act was signed ironically by President Ronald Reagan in August, 1988. To complete the legislation, in October, 1993, President Bill Clinton sent a letter of apology to Japanese American internment survivors along with their checks. William Hohri’s imprint was in that letter and on those checks. He was and is an American hero, a faithful Christian, and a friend of all peace-loving, freedom-loving people in the world. Thanks be to God for this good man.

The Rev. Martin Deppe, United Methodist Church, retired

November 18, 2010

William Hohri is an American hero. His life work was the repairing of America, and he succeeded by leading one of the most radical social justice movements culminating in redress almost half a century later for Japanese-American survivors of the illegal and unconstitutional concentration camps set up at the outbreak of WWII. Bill was 14 years old when he and his family were locked up at the Manzanar Camp in eastern California.

Bill did not forget that humiliating experience. That was still in the background when his local church in Chicago elected him a member of the regional body, the Northern Illinois Conference of the United Methodist Church. At these annual meetings Bill began to find his voice on social issues. This was in the late sixties, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and the American war in Vietnam. Bill chaired the Peace Division of the Conference Board of Christian Social Concerns, which I chaired and he also attended Renewal Caucus meetings where he sharpened his skills in political debate and in organizing around justice issues. Later he told me these experiences helped prepare him for the redress fight which

opened up for him just a few years later.

Bill had quick intelligence, an indomitable spirit and an uncommon courage. In the words of our long- time colleague, Rev. Gregory Dell, Bill was “in life, a giant of faithfulness and persistence.” I remember joining Bill, Yuriko, and their young daughters, Sasha and Sylvia for a car ride to Milwaukee to join an open housing march led by the local civil rights leader, Father Groppi. The marchers were predominantly African American. Along the route crowds of Caucasians shouted at us all manner of epithets, including “White Power.” Getting exasperated, Bill shouted back at them, “Yellow Power!” At Bill’s invitation I was privileged to join a team of Methodists, Bishop Jesse DeWitt and Revs. Martha Coursey and Gregory Dell, in testifying at the Chicago hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in late 1981. We Chicago area Methodists were proud of Bill and honored to be part of his national effort. Later, on one of his many speaking tours, as Chair of the National Council for Japanese American Redress, Bill did a radio show in Indiana. After his presentation he took calls from the radio audience and one male caller blurted out: “You sound like a Jap lover.” Bill was so stunned he was speechless, something unusual for him by this time. The next Sunday he reported to his congregation, Parish of the Holy Covenant, on his week’s tour and confessed that he should have responded to the caller, “Yes, I loved my Jap mother, my Jap father and the rest of my Jap family.”

The movement had highs and lows, but through it all Bill had the vision, courage and perseverance to carry on against unexpected opposition and tremendous odds, leading to victory, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, offering $20,000 to each internee of Japanese descent. The Act was signed ironically by President Ronald Reagan in August, 1988. To complete the legislation, in October, 1993, President Bill Clinton sent a letter of apology to Japanese American internment survivors along with their checks. William Hohri’s imprint was in that letter and on those checks. He was and is an American hero, a faithful Christian, and a friend of all peace-loving, freedom-loving people in the world. Thanks be to God for this good man.

The Rev. Martin Deppe, United Methodist Church, retired

November 18, 2010

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Rafu Shimpo Article

Please click this link to read the Rafu Shimpo article (11/16/2010) about William Hohri: article

Diana Morita Cole

The first time I saw William, he was acting in a one-man, one-act Christmas play he’d written for our church. He strode up the centre aisle of our sanctuary, a total stranger, wearing a checked red and black logger’s jacket. I stared, a teenager then, at the bold figure who took over the proscenium as had no other at the Christian Fellowship Church in Chicago where I was a member. He stood behind the pulpit, but instead of speaking in soft modulated tones, William considered the small plastic fir in front of him, his one stage prop, and decried the hollowness, the shallowness of using a pagan symbol to promote industry at a time of spiritual awakening.

I was transfixed. Here was a new, disquieting voice of my older siblings’ generation, a voice questioning the significance of a religious icon that attenuated our enlightenment. We, my nieces and I, were silent on the drive back to our homes that evening. I don’t think anyone knew what to make of the stranger in our midst, but I was fascinated. I knew a current of change had just flowed into my life and into our small Nikkei community, but I had no idea how transforming that new riptide would become.

A few months later, just as boldly, William appeared in the meeting room where our youth group met for Bible studies. He was wearing his signature bowtie when he announced to Kerrie Takagishi, Donna Kaneko, Margaret Murata and me that he was to be our new Sunday School teacher. He stunned us as he began the first lesson by asking, “If a tree falls in the forest, and if no one is there to see it fall, does it make a sound?”

And so we met each Sunday, each girl wondering, I’m sure, what he might say next. William told us about Jesus and how He transformed Judaism and society by questioning tradition and by extending salvation beyond parochial boundaries to Jew and non-Jew alike—to anyone willing to listen to his teachings. During that year and after, William spoke to us as though we were his equals with the expectation we would respond to his teachings as intellectuals. His discussions never stooped to sentimentality. William’s intellectual range and moral sensibilities extended beyond commonly held strictures about sin, which he attributed to personal failing. As a teacher committed to intellectual discovery and rational thought, he taught us by his example to discern, to read, to support the arts, and to pursue meaning over value.

William was undeniably unconventional, and he was open--sharing his beliefs and the intimate stories of his life like no other adult I‘d met. He told me once, during our many after-service conversations when he was no longer officially my teacher, his thoughts about romantic love. Looking at me through his horned-rimmed glasses, he said he’d decided long ago that romantic love had no place in marriage. Instead, he thought marriage should be based on rational choice rather than on fleeting emotion. So as a diligent, stalwart young man, William surprised many women he met by inquiring whether they might be interested in marriage—with him, in particular, before he’d even asked them out on a date. And Yuriko, his prudent wife of almost 60 years, was the first to say yes.

William understood that institutions, like marriage, often required refinement, and like Jesus, William knew institutions were fallible, that individual morality was often superior to the ethics of our institutions—sometimes of the church, and often times our government. He believed, like his hero Robert Maynard Hutchins, that people should be educated for citizenship, educated to further the public good and not for a particular profession.

A few years after my husband and I left for Canada, William resigned his membership in the Christian Fellowship Church because its leadership and congregants didn’t support his opposition to the Vietnam War. He and Yuriko then joined the Parish of the Holy Covenant led by Rev. Martha Coursey, who openly invited gays and lesbians into the tiny community. Eventually, after his move to California, William became, as he said, “unchurched.”

He once wrote in his collection of letters called The Epistolarian, ``I often think the church's God-talk is terribly predictable. It's hard to tell whether the words are from inspiration or inertia.” William lived his life consistent with his beliefs, but he was rarely predictable, and he seldom lacked inspiration because he kept actively searching beyond political and religious ideology for new answers and universal truths.

He was the first person to tell me the Chinese culture was worthy of respect because “China,” he said, “developed a science and technology that matched, at times surpassed, that of the West up until the 19th century. In addition, many Chinese inventions were borrowed by the West and [were] crucial to the development of Western civilization.” Through the gleaning of his tireless intellect, he turned my attention to the world of Chinese religion and philosophy. William once postured, “If God is one and universal, then humankind's experience of God must be universal.”

Through his discourse, writing, and activism, he challenged his political and spiritual communities to question, to think critically, and then to act. William was relentless in his pursuit of justice and truth and in his commitment to improve American democracy.

William was endowed by birth with a religious orientation which informed his life and his thinking. It began with a father who was a Protestant minister, but William roamed far beyond the boundaries of his sire’s orthodoxy; William’s beliefs underwent continuing transformation from his youth and extended well into his seventies. In 1999 at the age of 72, he paid homage to Lao Tse in one of his many remarkable Epistolarian letters. He wrote,

“The Tao is nameless. God, too, is nameless. Of course, the Chinese experience of God is not the same as the Judeo-Christian experience. But even within the Judeo Christian tradition variations in experience are recorded. God is vengeful and violent as well as merciful and compassionate. The story of Abraham and Isaac even suggests human sacrifice was once given to God. And God was transformed by Platonic and Arab Aristotelian philosophy. At the same time, God took on some of the hocus pocus and superstitions of folk religion. And God's name was mistakenly used to legitimate imperial conquest and human subjugation.”

Now, as we gather to reflect on the life of a great questioner and uncommon thinker, I look back fifty one years to the impressionable girl I once was, who on one winter’s night was captivated by the spirit of a man who marched up the aisle of my undeveloped consciousness to take stewardship over my conscience with a tender, irrepressible intellect that has changed both me and America forever.

Diana Morita Cole

Los Angeles, CA

November 21, 2010

Warrior of the Rainbow

IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM HOHRI

March 13, 1927 to November 12, 2010

Warrior of the Rainbow

March 13, 1927 to November 12, 2010

Warrior of the Rainbow

Though we travel separate paths, our journeys and our vision are one. As we, your friends and loved ones, go forth into the world to continue your battle with the forces of evil and injustice we will always remember your essence and the native American legend that says: the world will be ruled for 5000 years by evil and then for 5000 years by good; and the time for that change is coming when all the Warriors of the different colors of the Rainbow unite to make the change. We remember that…

The rainbow is a sign from Him/Her who is in all things. It is a sign of the Union of all peoples, like one big family. Go to the mountaintop, child of my flesh, and learn to be a Warrior of the Rainbow.

Like the kind native Americans of old who gave work to all and kept care of the poor, the sick and the weak, so the Warriors of the Rainbow shall work to build a new world in which everyone who can work shall work. None shall starve or be hurt due to the coldness and forgetfulness of men. No child shall be without love and protection and no old person without help and good companionship in his declining years.

Even as the wise chiefs are chose, not by political parties, not by loud talk and boasting, not by calling other people names, but by demonstrating always their quiet love and wisdom in council and their courage in making decisions and working for the good of all. So shall the Warriors of the Rainbow teach that in the governments of counsel, they shall seek truth and harmony with hearts full of wisdom and prefer their siblings to themselves.

Great are the tasks ahead, terrifying are the mountains of ignorance, and hate and prejudice, but the Warriors of the Rainbow shall rise as on the wings of the eagle to surmount all difficulties. They will be happy to find that there are new millions of people all over the earth ready and eager to rise and join them in conquering all barriers that bar the way to a new and glorious world.

We have had enough now of talk. Let there be deeds!

May God grant you Peace and continue to light your path.

Just another Rainbow Warrior…..

Los Angeles

21 November 2010

21 November 2010

Nicholas V. Chen

Bill Hohri taught me about courage. He taught me about commitment and steadfastness in the face of seemingly impossible odds. Initiating and sustaining a class action law suit against a powerful government in its own courts to seek redress for a massive state sponsored violation of all the basic freedoms and rights guaranteed by the Constitution was not an insurmountable challenge to Bill.

He saw the need to raise and defend the sanctity of the rule of law, fairness, due process and equal protection, which are fundamental pillars of the American promise. He knew the message was just and strong, and that people would rally to this ideal. In fact, he brought together many people from across the spectrum to make a statement and help defend these values. That courage, that resolve, and that clarity to defend what is right is what made Bill Hohri "Master Yoda" to me.

He knew that the law would protect the future and that he and others would join together to protect the law. He knew that the forces of the empire would be formidable. Bill Hohri won that battle, since he secured the hearts and minds of many with the NCJAR lawsuit. The battle was not to be won or lost by scoring legal points. The battle was won and lost by taking the moral high ground and educating the people and the government that such conduct would be subject to the people’s and history’s accountability.

This was not an issue of Japanese Americans nor Asian Americans nor just Americans; this was a battle for right vs. wrong, of good vs. evil, for inoculating a society that throughout its short history has desperately needed booster shots. Bill Hohri not only spearheaded this necessary periodic vaccination; he trained a portion of the next generation of medics to pass on his tonic and treatments.

His uncompromising commitment to fundamental human rights and the freedoms that make America special were enhanced, not eroded, by the adversities of E.O. 9066. The crucible that forged our teacher Bill Hohri was the massive injustice perpetrated on Japanese Americans by a government that smothered freedoms in the dark cloak of national security. I know that the current day attempts to erode the rights and freedoms of other “suspect classifications” help reaffirm that Bill Hohri’s life’s work remains our responsibility; it is our obligation and our responsibility to uphold the motto that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Bill Hohri was master Yoda to me. His “force” runs strong still. He taught us that the Ronin need not fear the odds, nor the journey, nor the struggle. My teacher, friend and older brother Bill Hohri taught me and others that one’s conscience is one’s compass.

As you travel to the other side, Master Yoda, know that this day we teach our sons and daughters about the 47 Ronin and the modern day champions of the most important values of life. You have changed us and shaped us and crafted us to be the moral persons we strive to be.

Thanks for the precious lessons of life dear Master. We will wield our light sabers for the forces of good as you would want.

May the Force be with you Bill, and we will see you on the other side of the rainbow, dear friend.

Dale Minami

William Hohri brilliant, uncompromising, and totally dedicated to the idea that the United States should pay for its disgraceful treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. We travelled on parallel paths toward Redress and our paths crossed many times. While we employed the coram nobis petitions to overturn the convictions of the 3 men whose Supreme Court cases in 1943 and 1944 justified the imprisonment, William and his group went directly at the United States government for monetary relief. It was a movement of pure rebellious genius and influenced the course of our cases and the legislation that eventually resulted in Redress. He did not suffer fools lightly nor folks who criticized his vision but that single-minded determination gave our community and our nation a gift of strengthening our civil rights.

Phil Tajitsu Nash

William Hohri will be remembered in history for the Hohri versus United States class action lawsuit that he and others brought to win judicial redress for Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated en masse during World War II. While the case did not prevail due to technicalities, I can say from first hand experience as a lobbyist on Capitol Hill in the early 1980s that this case was the hammer over the heads of Congress that allowed them to tell their constituents that they voted for the $20,000 per person redress bill rather than wait for the $220,000 per person class action to prevail.

William's decision to lead the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), which brought the class action case, emerged from years of social justice and anti-war activism. He knew that waiting for elected officials to do the right thing had not worked during World War II, so he pushed for a court-based strategy. He joined with a Seattle-based Japanese American group, convened a support group in Chicago, and communicated regularly with supporters in California, New York, and Washington, D.C. He envisioned a strategy that called for "47 Ronin" (from the Japanese fable of that name) to make an extraordinary sacrifice by giving $1,000 to pay for the class action suit. He kept us all informed by writing monthly newsletters to supporters all over the country in the pre-internet era.

William was extraordinarily kind and friendly, but his attention to principle could sometimes be abrupt. For example, I still remember his letter to the NY Nichibei in the early 1980s criticizing my naive call for an apology and a group-based remedy for the wartime injustice. I had called for a monument, and he said (correctly) that an injury to individuals requires a remedy that compensates individuals. He made his famous comment about wanting to buy a car with his redress money, which at first shocked me and then made me see the light. My mom reminded me of this when she herself used her redress money to buy a Toyota Camry several years later!

In sum, William was one of many Nisei who proved that the "quiet American" stereotype was far from true. He used his considerable intelligence, writing skill, and leadership ability to galvanize a social justice movement that helped the Japanese American community get the redress it deserved. I hope that people will read his book, Repairing America: an Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress to get more insights into his life.

William's decision to lead the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), which brought the class action case, emerged from years of social justice and anti-war activism. He knew that waiting for elected officials to do the right thing had not worked during World War II, so he pushed for a court-based strategy. He joined with a Seattle-based Japanese American group, convened a support group in Chicago, and communicated regularly with supporters in California, New York, and Washington, D.C. He envisioned a strategy that called for "47 Ronin" (from the Japanese fable of that name) to make an extraordinary sacrifice by giving $1,000 to pay for the class action suit. He kept us all informed by writing monthly newsletters to supporters all over the country in the pre-internet era.

William was extraordinarily kind and friendly, but his attention to principle could sometimes be abrupt. For example, I still remember his letter to the NY Nichibei in the early 1980s criticizing my naive call for an apology and a group-based remedy for the wartime injustice. I had called for a monument, and he said (correctly) that an injury to individuals requires a remedy that compensates individuals. He made his famous comment about wanting to buy a car with his redress money, which at first shocked me and then made me see the light. My mom reminded me of this when she herself used her redress money to buy a Toyota Camry several years later!

In sum, William was one of many Nisei who proved that the "quiet American" stereotype was far from true. He used his considerable intelligence, writing skill, and leadership ability to galvanize a social justice movement that helped the Japanese American community get the redress it deserved. I hope that people will read his book, Repairing America: an Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress to get more insights into his life.

Ronald Low

Great are the mountains of hate, injustice and ignorance. But for the "Warriors of the

Rainbow" the "force" will always be with them, so that no task is insurmountable, or

challenge too great. And if the task has not been completed by the time one's journey

must come to an end, it will simply be picked-up by his brethren so no ground will be

lost.

Rainbow" the "force" will always be with them, so that no task is insurmountable, or

challenge too great. And if the task has not been completed by the time one's journey

must come to an end, it will simply be picked-up by his brethren so no ground will be

lost.

Ellen Godbey Carson

William Hohri

America has lost a true hero. William Hohri was a courageous and prophetic voice for redress for Americans of Japanese ancestry.

In 1942, at age 15, William Hohri and his family were exiled from their home in California and subsequently incarcerated at Manzanar, California for over three years, solely because of their Japanese ancestry. The Hohris and approximately 120,000 other Americans of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast were imprisoned and deprived of virtually every one of their constitutional rights by the US Government.

Mr. Hohri sought recognition of the Government's injustices, to save other minorities from experiencing similar injustices. He never allowed threats, personal attacks or political opposition to sway him from this pursuit of justice.

While others pursued political reform in Congress, Mr. Hohri had an unwavering belief that the federal court system was the appropriate place to seek redress for constitutional violations. The courts, after all, have the ultimate duty to protect the constitutional rights of minorities, particularly when the political majority has failed to do so.

As Chairperson of the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), Mr. Hohri spearheaded a legal quest for redress. Combining the dedication, energy and talents of AikoYoshinaga-Herzig (a dedicated archivist) and other NCJAR members and supporters, his group made an extraordinary effort to bring to light the egregious facts of the government's wartime actions.

In 1983, Mr. Hohri filed a class action lawsuit against the United States of America, seeking an apology and monetary redress on behalf of all Americans of Japanese ancestry who faced these unprecedented violations of their constitutional rights during World War II. The lawsuit demonstrated fraud, concealment, and uncontrolled racism in the wartime actions against Japanese Americans. It sought monetary redress, a declaration of wrongdoing, and most importantly, a reversal of the dangerous precedent created by the U.S Supreme Court's wartime cases, which condoned the exile and imprisonment of an entire race of people solely because of ancestry. The case twice went before the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking the high court's recognition of these egregious wrongs.

The lawsuit was ultimately denied on procedural grounds. Mr. Hohri always knew that was a major risk. But it that never swayed him from his commitment to do everything humanly possible to seek redress. That is all one can ever do, and he dedicated his life to the task. His efforts helped create public attention and pressure on Congress to enact an apology and monetary redress for Americans of Japanese ancestry injured by the wartime actions. His leadership brought a new sense of courage, pride and activism to the Japanese American community. He inspired others to become civil rights activists on broader issues. He helped bring truth to the historical account of this era in American history in a way that makes us all stronger. Many persons who never before had the courage to speak about their wartime experiences suddenly found a voice. Cathartic healing occurred as people shared their experiences in the hope they could help prevent having similar injustices ever inflicted on others.

Mr. Hohri was a transformational agent in helping the AJA community find strength, dignity and honor from such sad experiences. A prolific writer, scholar and philosopher, he challenged people to think, to act on their beliefs, to be fearless in their approach to life, and to challenge injustices around them.

I was very blessed to work with William Hohri as one of the attorneys on his case. All of us who knew him know we have lost a true American hero. We are all stronger for his dedication to justice.

Submitted by Ellen Godbey Carson, ecarson@ahfi.com,

700 Richards St., #2601, Honolulu, HI 96813 (808) 223-1800c (808)524-1800work

The comments above may be used in whole or in part, to assist in any public notice, editorial comments, eulogy or obituary regarding William Hohri.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)