The first time I saw William, he was acting in a one-man, one-act Christmas play he’d written for our church. He strode up the centre aisle of our sanctuary, a total stranger, wearing a checked red and black logger’s jacket. I stared, a teenager then, at the bold figure who took over the proscenium as had no other at the Christian Fellowship Church in Chicago where I was a member. He stood behind the pulpit, but instead of speaking in soft modulated tones, William considered the small plastic fir in front of him, his one stage prop, and decried the hollowness, the shallowness of using a pagan symbol to promote industry at a time of spiritual awakening.

I was transfixed. Here was a new, disquieting voice of my older siblings’ generation, a voice questioning the significance of a religious icon that attenuated our enlightenment. We, my nieces and I, were silent on the drive back to our homes that evening. I don’t think anyone knew what to make of the stranger in our midst, but I was fascinated. I knew a current of change had just flowed into my life and into our small Nikkei community, but I had no idea how transforming that new riptide would become.

A few months later, just as boldly, William appeared in the meeting room where our youth group met for Bible studies. He was wearing his signature bowtie when he announced to Kerrie Takagishi, Donna Kaneko, Margaret Murata and me that he was to be our new Sunday School teacher. He stunned us as he began the first lesson by asking, “If a tree falls in the forest, and if no one is there to see it fall, does it make a sound?”

And so we met each Sunday, each girl wondering, I’m sure, what he might say next. William told us about Jesus and how He transformed Judaism and society by questioning tradition and by extending salvation beyond parochial boundaries to Jew and non-Jew alike—to anyone willing to listen to his teachings. During that year and after, William spoke to us as though we were his equals with the expectation we would respond to his teachings as intellectuals. His discussions never stooped to sentimentality. William’s intellectual range and moral sensibilities extended beyond commonly held strictures about sin, which he attributed to personal failing. As a teacher committed to intellectual discovery and rational thought, he taught us by his example to discern, to read, to support the arts, and to pursue meaning over value.

William was undeniably unconventional, and he was open--sharing his beliefs and the intimate stories of his life like no other adult I‘d met. He told me once, during our many after-service conversations when he was no longer officially my teacher, his thoughts about romantic love. Looking at me through his horned-rimmed glasses, he said he’d decided long ago that romantic love had no place in marriage. Instead, he thought marriage should be based on rational choice rather than on fleeting emotion. So as a diligent, stalwart young man, William surprised many women he met by inquiring whether they might be interested in marriage—with him, in particular, before he’d even asked them out on a date. And Yuriko, his prudent wife of almost 60 years, was the first to say yes.

William understood that institutions, like marriage, often required refinement, and like Jesus, William knew institutions were fallible, that individual morality was often superior to the ethics of our institutions—sometimes of the church, and often times our government. He believed, like his hero Robert Maynard Hutchins, that people should be educated for citizenship, educated to further the public good and not for a particular profession.

A few years after my husband and I left for Canada, William resigned his membership in the Christian Fellowship Church because its leadership and congregants didn’t support his opposition to the Vietnam War. He and Yuriko then joined the Parish of the Holy Covenant led by Rev. Martha Coursey, who openly invited gays and lesbians into the tiny community. Eventually, after his move to California, William became, as he said, “unchurched.”

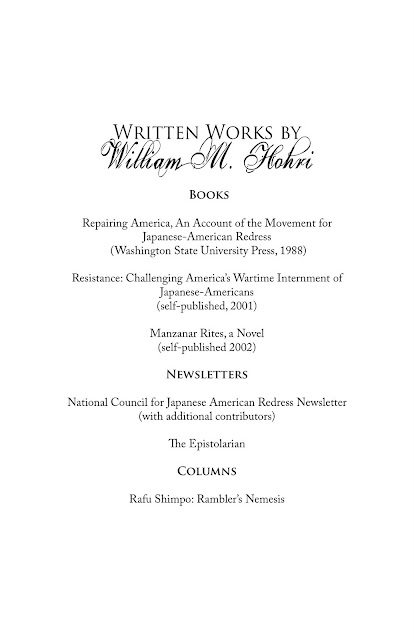

He once wrote in his collection of letters called The Epistolarian, ``I often think the church's God-talk is terribly predictable. It's hard to tell whether the words are from inspiration or inertia.” William lived his life consistent with his beliefs, but he was rarely predictable, and he seldom lacked inspiration because he kept actively searching beyond political and religious ideology for new answers and universal truths.

He was the first person to tell me the Chinese culture was worthy of respect because “China,” he said, “developed a science and technology that matched, at times surpassed, that of the West up until the 19th century. In addition, many Chinese inventions were borrowed by the West and [were] crucial to the development of Western civilization.” Through the gleaning of his tireless intellect, he turned my attention to the world of Chinese religion and philosophy. William once postured, “If God is one and universal, then humankind's experience of God must be universal.”

Through his discourse, writing, and activism, he challenged his political and spiritual communities to question, to think critically, and then to act. William was relentless in his pursuit of justice and truth and in his commitment to improve American democracy.

William was endowed by birth with a religious orientation which informed his life and his thinking. It began with a father who was a Protestant minister, but William roamed far beyond the boundaries of his sire’s orthodoxy; William’s beliefs underwent continuing transformation from his youth and extended well into his seventies. In 1999 at the age of 72, he paid homage to Lao Tse in one of his many remarkable Epistolarian letters. He wrote,

“The Tao is nameless. God, too, is nameless. Of course, the Chinese experience of God is not the same as the Judeo-Christian experience. But even within the Judeo Christian tradition variations in experience are recorded. God is vengeful and violent as well as merciful and compassionate. The story of Abraham and Isaac even suggests human sacrifice was once given to God. And God was transformed by Platonic and Arab Aristotelian philosophy. At the same time, God took on some of the hocus pocus and superstitions of folk religion. And God's name was mistakenly used to legitimate imperial conquest and human subjugation.”

Now, as we gather to reflect on the life of a great questioner and uncommon thinker, I look back fifty one years to the impressionable girl I once was, who on one winter’s night was captivated by the spirit of a man who marched up the aisle of my undeveloped consciousness to take stewardship over my conscience with a tender, irrepressible intellect that has changed both me and America forever.

Diana Morita Cole

Los Angeles, CA

November 21, 2010